This past spring the Bell Museum of Natural History broke ground at the site of its future home on the University of Minnesota's St. Paul campus. Slated to open in summer 2018, the newly renamed

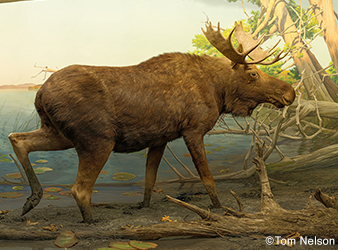

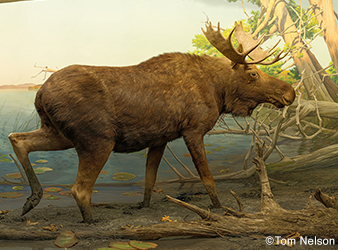

Bell Museum + Planetarium will host state-of-the-art exhibits and showcase many of the historical dioramas for which the Bell is internationally renowned.From 1911 to 1964, some of the nation's finest artists and taxidermists—including Francis Lee Jaques, John Jarosz, and Walter Breckenridge—collaborated to create these beautiful, true-to-life scenes of the state's varied landscapes. Captured behind the glass of the dioramas are moments in time—gray wolves on Superior's rocky shore in late winter, migrations of snow geese and sandhill cranes in western Minnesota, a bull moose at the edge of a northern lake, shorebirds working the water's edge at Lake Pepin, nesting passenger pigeons—all faithfully and artistically rendered. Taxidermied mounts blend seamlessly with painted backdrops, giving the viewer the sense of being there as events are unfolding.

Article continues below sidebar

Wide Angle

See

more images of the Bell Museum of Natural History dioramas.

The dioramas' designers, whose work was compelled by a conservation ethic, would surely agree with present-day museum curator Don Luce: "A diorama draws attention to these places: to their beauty, to their magic, to their importance, to their history. For many people, it offers a connection they might never otherwise have had. You need to know that something exists in order to care about its preservation."The dioramas depict real places and wildlife populations in Minnesota, many of which have experienced dramatic changes. For ecologists and for all of Minnesota's citizens, these scenes grow more relevant with time, offering a reference point for understanding ecological change and a reminder of the state's invaluable natural heritage.

Gray Wolves, Superior's North Shore

A trio of gray wolves—two males, a female. One is nose down, picking up a scent; the others are heads up, ears forward, focused on something in the distance. Their physical power is evident. At the same time, this family group conveys a certain vulnerability—set against the backdrop of sheer cliffs, patches of late winter snow, and Lake Superior roiled by an incoming squall. The wolves don't dominate the scene so much as belong to it.Built between 1940 and 1942, this diorama was designed to counter the impression of wolves as vicious vermin best destroyed, little more than cash in the pockets of bounty hunters. Businessman and conservationist James Ford Bell had a keen interest in wolves. He made a donation for this diorama and a good part of the museum to house it."It was bold at the time to convey wolves this way," says Chel Anderson, co-author of

North Shore and an ecologist with the Department of Natural Resources. "More people now see their value as a keystone predator."The landscape co-stars in this diorama with its dramatic setting at Shovel Point. Visitors to the site today are indebted to the DNR, conservation groups (most notably The Nature Conservancy), and legislators whose efforts led to purchase of a private preserve and expansion of Baptism River State Park into Tettegouche State Park in 1979.DNR wolf management specialist Dan Stark estimates the state's current wolf population at 2,278. It's appropriate that the diorama depicts them on the shore in a winter scene, notes Stark, since that's when deer move closer to the lake. Careful observers will find that Francis Lee Jaques painted the background with a lone deer: the object of the wolves' attention.For University of Minnesota forest ecologist Lee Frelich, the diorama brings a number of real-world changes to mind. The birches depicted in the diorama seem typical of a North Shore scene. "In the early '40s, birch and aspen forests were very young, having started after cutting of white pine followed by burning the slash," says Frelich. Since that time, birch forests have declined along the shore, only partly due to old age. "Increased drought frequency in the last decade, along with earthworm invasion," he notes, "has probably caused accelerated death for many of the trees. Birch roots are very sensitive to soil temperature, which gets higher during droughts and with the longer warming period related to the earlier springs of recent years." Earthworms add to the problem by reducing the insulating duff layer over the soil.Frelich also notes that the whitetail deer depicted in the diorama has taken on new meaning with time. "White pine, spruce, and balsam would typically succeed birch forest, but today there is little reproduction beneath the dying birches due to lack of a white pine seed source and winter overbrowsing by deer." Spreading red maples represent a new story in the understory along the North Shore, reflecting a warming climate.Unchanged since the diorama's creation is the raw force of Lake Superior. Anderson says, "I appreciate that the diorama depicts Superior as dynamic rather than placid, since that's really what created this coastal environment."Asked if she would change anything in the diorama, she ponders. "Maybe the painting of Shovel Point could use a little more color on the red end of the spectrum? Some pink and orange: for the cryptoendolithic micro-organisms that live between the crystals of the minerals."After all these decades, the diorama still invites us to look at the landscape with new eyes.

Migration of Snow Geese

It is 1942, the setting a spring evening at Mud Lake near Wheaton along the Minnesota–South Dakota border. In the foreground are 20 mounted specimens of lesser snow geese, a white-fronted goose, a mallard, and three pintails, all collected from the area and later prepared by Walter Breckenridge, then curator of the museum. The background was painted by Francis Lee Jaques, renowned for his work as an exhibit artist with the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.Standing before the diorama, current curator Don Luce enthuses: "Many people consider this the finest bird diorama in the country. The background painting is one of the hallmarks of Jaques' career. Note the merging of foreground and background, the color palette, the sense of motion conveyed by the position of the birds—and see how he has captured the quality of the light."The diorama is side-lit to convey the low, raking light of evening. Water is represented by nickel-plated copper, which in turn reflects a ceiling painting of sky filled with multitudes of birds. Such exquisite detail is worth a long, lingering look.Beyond visual artistry, a natural history diorama is ultimately about the stories it sparks. Although physical elements behind the glass are permanently fixed, they take on new meaning with passing time. Perhaps no exhibit illustrates this to a greater degree than does this snow goose diorama. In their wildest dreams, its designers could not have foreseen how dramatically its real-world context was to change.First: taxonomy. When first conceived, the exhibit was to highlight migration of the blue goose, then considered a distinct species. But Breckenridge was aware of a debate percolating among taxonomists as to whether "blues" and "snows" were one and the same species. In the exhibit, he gave a nod to the possibility by featuring a mixed pair. Not until four decades later were the two birds formally recognized as morphs of a single species, the blue being a color variant of the snow. Without the stroke of a paintbrush or the birds moving a muscle, the diorama had a new story to tell.In April 1942 the design team headed to Traverse County in their preparations for the exhibit. The marshy Mud Lake was a well-known destination for viewing the spectacle of bird migration. Prime time was in spring, when the snow geese were en route from wintering sites along the Gulf Coast to breeding grounds in Canada.Breckenridge's account of the trip (

The Flicker, October 1942 issue) describes how he and Jaques "poled, rowed and waded into the middle of the extensive swamp land called Mud Lake." They secured birds for the exhibit (with necessary permits), then photographed and sketched the scene, which included "50,000 milling geese, 500 austere and deliberate white pelicans, 200 majestic whistling swans, and myriads of courting ducks."If the diorama is inspiring to behold, it is because those who created it were inspired by what they saw. Breckenridge writes: "What an experience to put up clouds of tens of thousands of these big waterfowl! … As we moved in toward the mass of resting geese the nearer birds craned their necks, then rose in a gabbling crowd. Then, like the domino row in reverse, the next farther birds arose, then the next and the next till the whole sky seemed full of wheeling wings."In the moment captured in the diorama, the birds and landscape are felt as wholly intertwined: the expression of an old, old story. Year upon year, the geese had found what they needed in this wide, flood-prone valley with its shallow lakes and wetlands.As it turns out, this landscape was on the cusp of major change. Water levels once determined by rain and snowmelt were about to become the business of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. A long-awaited flood control project was substantially complete. With Reservation and White Rock dams, the land would be spared widespread seasonal flooding. In the process, a large part of the area's vast marsh would be destroyed.Before the decade was out, the snow geese and Mud Lake had substantially parted ways. They are still seen in the area—occasionally in large numbers—but never again with the regularity that they once were.Later efforts to restore Mud Lake's waterfowl habitat included a truly herculean bistate project in the 1980s, bolstered by sportsmen's groups and neighboring landowners. Periodic partial drawdowns to give wetland vegetation a chance to re-establish have been moderately successful."Restoration of habitat," says DNR area wildlife biologist Kevin Kotts, "remains a challenging prospect, especially on the more exposed eastern [Minnesota] shoreline, which takes the brunt of windblown waves."Must the Bell's diorama then be interpreted as a requiem for the snow goose? Not by a long shot. Follow the story; follow the geese. Today, people hoping to experience the migration often head to Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge in South Dakota. Bill Schultz, retired refuge wildlife biologist, describes snow geese in a word—

adaptive. Adaptive, to be sure. Recent estimates put the midcontinent population at an astonishing 12.4 million birds.According to research scientist Ray Alisauskas of the Canadian government's environment and climate change agency, the birds' ability to exploit agricultural activity and their expansion into new breeding areas contributed to the boom. The large populations have damaged sensitive environments along Hudson Bay and in the Canadian Arctic. Many states have instituted spring hunts and liberal harvest limits. Still, snow geese populations continue to increase.Nevertheless, the wonder of migration has continued to inspire awe. Schultz recalls people like Anne Williams of Duluth returning year after year to photograph the birds and record their calls: "It was a kind of pilgrimage for her and for many others."As in Lewis Carroll's

Through the Looking-Glass, the diorama offers viewers entry to a marvelous, sometimes perplexing place where blue geese become snow geese, where lakes become reservoirs, where almost inconceivable numbers of geese stream like tributaries across the sky, birds of both grandeur and devastation. Like Alice, we inevitably find ourselves reflected in the glass.

Spring in the Big Woods

Completed in 1949, this diorama was inspired by 28-acre Maplewood Park in Waseca, a city park where a high, forested peninsula juts into Clear Lake. Maplewood has a storied past. In the 1880s it hosted an upscale hotel and cabins (one owned by Rochester's Mayo brothers), as well as a nationally touring summer chautauqua. This diorama highlights the site's equally compelling natural history as part of the legendary 2,000 square miles of the Big Woods. Less than 2 percent of this ecosystem remains, but those who grew up within reach of a mature maple-basswood forest will recognize the diorama's dappled light, blanket of early spring wildflowers, and branches filled with songbirds just returned after a winter's absence.DNR plant ecologist Derek Anderson first visited Maplewood while doing fieldwork for the Minnesota Biological Survey in 2008. "Mature sugar maples and basswood in the canopy, a mix of ages, standing and downed trees in various stages of decay, a diverse understory: It was what you hope to see," he says.Those values remained when Anderson recently returned and was met with the call of a barred owl. Less encouraging was an area of bare soil atop the hill, a small moonscape of sorts lacking the rich diversity of the surrounding forest. "Likely earthworms," Anderson conjectures, citing research undertaken on similar sites by Cindy Hale of the Natural Resources Research Institute. Classic Big Woods wildflowers such as violets and trilliums can be negatively impacted when these nonnative worms consume soil-enriching leaf litter.For University of Minnesota researcher Rebecca Montgomery, the diorama offers potential insights into the impact of climate change on the state's diverse ecosystems. Montgomery coordinates the Minnesota Phenology Network, in which professional and citizen scientists use historical data sets as reference points to track natural events such as bloom time of flowers, tree leaf-out, insect emergence, and arrival and departure dates of migrant birds. Has the timing of such phenomena shifted in response to (or independent of) climate change? In some respects, the diorama's setting of a day in early May 1949 looks a lot like a day in early April 2016 at Maplewood Park. "To the degree that a diorama is biologically and phenologically accurate, it can offer clues, like a historical photo," says Montgomery.Conservationist and cartoonist Al Batt lives near Maplewood and has led innumerable bird and wildflower trips there. As a student in the late 1960s and early '70s, he spent countless hours at the Bell Museum. "I ate sandwiches in front of those dioramas," Batt says, "sometimes between classes and sometimes when I should have been in class. They are so well done that my imagination put me in the diorama. It was a glorious moment when I could be two places at once. Good dioramas imitate real life. They are postcards from home."

Editor's note: Visit the Bell Museum of Natural History before it closes Dec. 31, 2016. The new museum opens summer 2018. Learn more about how climate change is affecting Minnesota's lands, waters, and wildlife through the Minnesota Phenology Network.